- February 25, 2026

- Updated 12:56 pm

Mind the map!

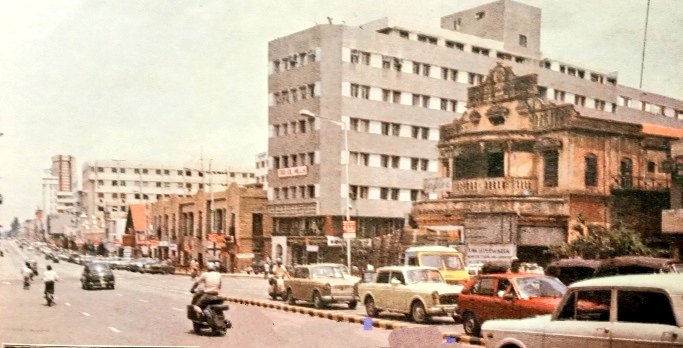

Strap: Bangalore’s 1983 map resurfaces, revealing a city where Indiranagar was missing & Jayanagar marked its throbbing heart

Blurb:

The vintage 1983 map didn’t just spark nostalgia—it revealed how Bangalore’s hotspots have shifted over the decades. While it marked familiar landmarks like MG Road, Shivajinagar & Whitefield, one detail stood out – South Bangalore looked far more developed than its northern half

Byline: Bindu Gopal Rao

It all began from a social media post by a vice chairman of a start-up foundry on August 30. She wrote, “We bought Bengaluru’s map (1983 edition) from a collector, and it turns out HSR & Indiranagar are non-existent. Jayanagar is almost central to the city.”

That’s it. In the next couple of hours, social media went on an overdrive with posts deep in nostalgia, longing, and wistful throwbacks. Old-timers recalled wide roads lined with flowering trees, when “traffic jam” wasn’t in Bangalore’s dictionary, and when water from the tap was as sweet as Cauvery herself. Younger Bangaloreans, many born after the IT boom, marvelled at how different the city looked just four decades ago.

The vintage 1983 map didn’t just spark nostalgia—it revealed how Bangalore’s hotspots have shifted over the decades. While it marked familiar landmarks like MG Road, Shivajinagar, and Whitefield, one detail stood out – South Bengaluru looked far more developed than its northern half.

Back then, Jayanagar was almost the city’s beating heart, while Indiranagar barely existed on the map. Cut to today, and both areas define the city’s modern identity—one rooted in old-world charm, the other in buzzing urban culture. To understand this transformation, we spoke to old-timers who’ve lived the journey. Here’s what they told us…

Jayanagar: The Newcomer

For longtime residents, Jayanagar was once considered one of Bangalore’s “newer” localities. Old-timers who grew up in the 1950s and 60s often recall that the true heart of the city lay in older neighbourhoods like Basavanagudi and Malleshwaram. Septuagenarian Parimala remembers Jayanagar as relatively new during her childhood. “My mother was quite dismissive of it—Basavanagudi was always the city’s soul for her. But for us, Jayanagar felt exciting and fresh, a place waiting to be explored,” she recalls.

Today, Jayanagar has transformed into a thriving commercial and residential hub, a prized address in Bangalore’s real estate map.

“I came to the city in 1974, when it truly lived up to its Garden City tag. Jayanagar was then a posh neighbourhood, and owning a home there was a dream. It wasn’t as developed as now, but it had its own charm. Back then, BMTC buses were the only reliable transport. Now, the Metro connects the city seamlessly, from east to west and north to south, and private transport options abound. The presence of software giants like Infosys and Wipro nearby has only boosted Jayanagar’s stature,” says Mohan Baichwal, a retired ISRO employee.

Baichwal reflects with pride on his time at ISRO. “Our satellite technology contributed to the planning of the Outer Ring Road, which became pivotal in Bangalore’s expansion. The city has since grown into one of India’s fastest-developing urban centres, with vibrant neighbourhoods like Jayanagar, Indiranagar, and Koramangala shaping its modern identity,” he adds.

Village to vogue

The old city map makes no mention of Indiranagar as we know it today—now one of Bangalore’s most upmarket addresses. For 84-year-old Kantha Rao, the memory of the area is very different. “This was where the isolation hospital for TB patients stood. It was nothing like what it has become today,” he recalls.

Interestingly, Indiranagar, named after former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, only came up in the early 1970s when the Bangalore Development Authority (BDA) developed it as a planned layout. “In those days, it was little more than a village. People rarely went beyond Ulsoor, which was considered the edge of the city. Today, that very area has transformed into one of Bangalore’s poshest localities,” notes Baichwal.

But the city’s rapid urbanisation hasn’t set well with many older residents, who argue it has been poorly planned. R Raja Chandra, a Bangalorean for over 50 years, points out that after Jayanagar and Rajajinagar were developed in the late 1940s, the City Improvement Trust Board (CITB) merely kept expanding them by adding new stages. The Urban Land Ceiling (ULC) Act of 1976, he says, “choked development altogether,” while its repeal in 1999 opened the floodgates to rapid but unplanned growth.

He laments that the BDA failed in its role as a watchdog, leaving the so-called pensioners’ paradise without the world-class infrastructure it deserved. “Plans are short-lived and myopic,” he insists, adding that instead of chasing grandiose projects like sky decks and tunnel roads, the state should focus on mass transport, last-mile connectivity, and empowering residents’ associations to have a real say in city management.

As Bangalore expands and reinvents itself, many lament that the city’s old charm has faded. Yet, its heritage neighbourhoods remain a living link—connecting what the city was to what it is becoming.